Now, who will stand at my right hand and build the bridge with me?

Travelling across Sydney Harbour by ferry is an experience to behold.

The vessels that criss-cross the harbour today are a far cry from those first public ferries that struggled to serve the city’s growing population.

A better solution for moving people across the city was desperately needed and even though the ambition for a harbour bridge was evident for years, it would take a plague, four public design competitions and a determined futurist for it to become a reality.

The first designs for a permanent bridge crossing Sydney Harbour had been put forward as far back as 1840. That early proposal was for a floating structure, 45 feet wide, anchored by fixed chains and propelled by steam, supposedly at incredible speed, to move people and vehicles across the water.

The first public design competition was held in 1900, but as the city grew and political tides changed rapidly, none of these designs would come to fruition.

In 1815, the government architect and former convict Francis Greenway had written a letter to The Australian, arguing that such a bridge would:

…give an idea of strength and magnificence that would reflect credit and glory on the colony and the Mother Country.

Greenway’s plan had been to build a fort on Observatory Hill, with a supplementary fort on Dawes Point. He would then construct a bridge to the northern shore of the harbour.

There were other proposals: for floating bridges, a pontoon bridge, swing bridges, high-level bridges, seven-span bridges, tunnels and subaqueous tube tunnels.

It was even suggested at one time that the harbour itself could be filled in—a proposal which was thankfully met with short shrift among the public.

In 1880, the NSW Premier Henry Parkes had petitioned for a harbour bridge to be built in time to commemorate the first centenary of the colony, an anniversary which came and went with no such monument rising to meet that deadline. A commentator at the time noted to have stopped this

Someone must have been standing on Parkes’ right hand.

In 1890 a Royal Commission of Inquiry was called into the possible connection between the city and the North Shore. There were other pressing needs that supported the case for a harbour bridge.

The catalyst for action would not come from one person, but from hundreds. In the rapidly growing city, houses were crowded, streets congested and waterways bursting with people. Town planning had failed to keep up with the demands of the expansion, and with poor sewerage and overcrowding, conditions were ripe for disease.

On 19 January 1900, the first plague epidemic broke out in Sydney. In seven months 303 people were infected and of those 103 would die.

With 5 million passengers, 3,780,500 vehicles and 43,800 horsemen a year being moved by ferry, and the breakout of the bubonic plague in the early 1900s, it became clear that the rambling city of Sydney had grown like an untamed weed and was on the brink of being beyond control.

To bring order to this chaos, the city would need to start over. The entire remodelling of Sydney would offer an opportunity for the long-awaited bridge to rise.

Parts of North Sydney and Millers Point were demolished to remove the shanties and shacks that had dotted the point. In their place came plans for an underground railway system and the bridge that would finally join the two sides of the city.

The daunting amount of work to be done would make this the largest public works project ever attempted in New South Wales.

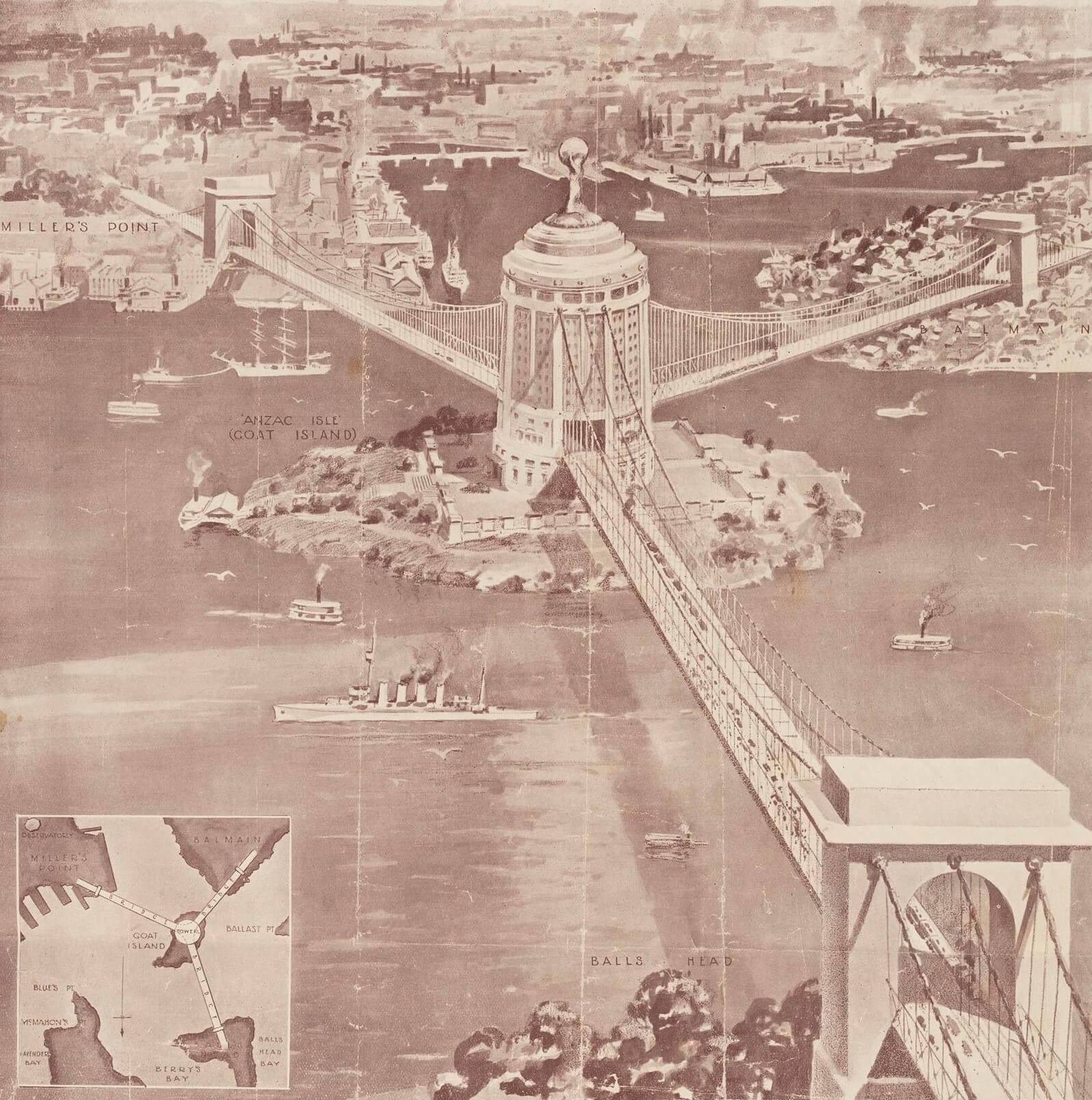

Between 1900 and 1924 the government would run four separate Bridge design competitions. By 1924, more than 20 designs had been submitted from national and international engineering companies; these were then exhibited in the Queen Victoria Markets, at what would be modern Sydney’s iconic Queen Victoria Building. But none of these hopefuls would succeed in meeting the rigorous demands of Sydney’s citizens—or its city planners.

The two strongest contenders to finally emerge were Norman Selfe and John Job Crew Bradfield, who each had different and ambitious visions for the harbour.

Selfe was an engineer, naval architect, inventor, urban visionary and advocate of technical education who had arrived with his family in Sydney in 1855.

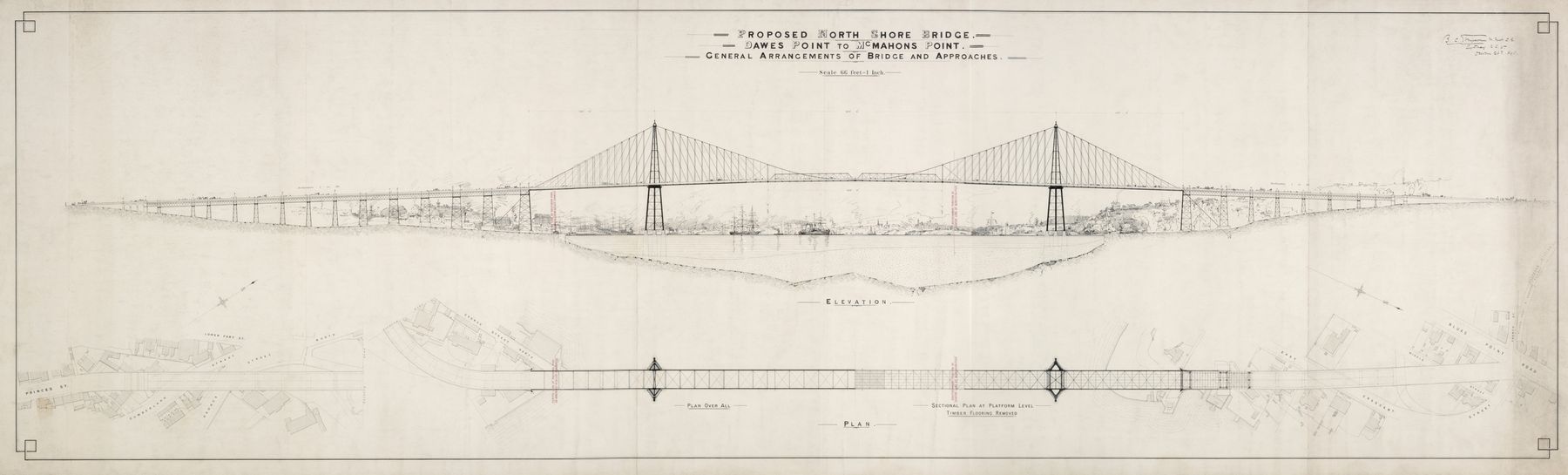

His planning dreams for Sydney were on a grand scale, and he had conceived of a harbour crossing decades before the Harbour Bridge we know today was built. For all his innovative ideas, Selfe was not hugely successful as a town planner in his lifetime, though many of his progressive visions were later realised. His 1901 design for a harbour bridge from Dawes Point to McMahons Point was accepted by the NSW Government—but it, too, was never built, falling prey to the city’s political tides. Selfe then won a second competition outright in 1903. He saw a steel cantilever bridge stretching from Dawes Point to McMahons Point. The selection board was unanimous in its praise:

The structural lines are correct and in true proportion, and … the outline is graceful…

Still, Selfe would not win. His vision would again be lost to the vagaries of Sydney’s economics and a change of government in 1904. In the end, Selfe would never even be given the £1100 prize he was entitled to, nor was he paid for his subsequent work on the plans, which he had estimated to be worth more than £20,000 at the time.

In his book published in 1908, Selfe wrote that the competition:

…has spelt ruin rather than reward to the successful competitor, and cast a dark shadow upon the fair name of New South Wales.

Instead, the man who would become synonymous with the Harbour Bridge was John Job Crew Bradfield, a civil engineer with a brilliant academic mind. Bradfield was a paradox: as a planner he was bold and visionary, but as an engineer he displayed caution.

He planned on a vast scale; and though his visions were futuristic, they had a notable old-fashioned look to them. In 1912, he submitted to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works a design for a cantilever bridge—a structure that projects into space, anchored at each end—from Dawes Point to Milsons Point, and was given the government’s approval. Before any kind of construction could begin, the country would be drawn into the First World War, where almost one million Australians would serve, over 27,000 would lose their lives and over 30,000 would be taken as prisoners of war.

In the years of global tumult that followed the end of the war, Bradfield travelled the world researching bridge designs. He would come upon an arch bridge that was suitable for the enormous span of Sydney harbour—and cheaper by at least £400,000 than a cantilever bridge. It was Hell’s Gate Bridge in New York City, a steel-through, single arch bridge crossing the East River between Astoria, Queens and the island of Manhattan.

Amongst the many who worked with Bradfield, the least known is Kathleen Butler. Her official title was Secretary, but she was also known as the ‘bridge girl’. Butler was Bradfield’s ‘eyes and ears’.

Mr Peach, a public works engineer on the Sydney Harbour Bridge, recalls Kathleen Butler:

She went overseas, with one of the groups of engineers from his staff, to examine possible tenders for construction of the Harbour Bridge… when she was back in Sydney she became aware that there was a movement on hand to recall Dr Bradfield and his staff and put a stop to any further work on the development of the bridge itself. They were going to send him a cable, she fortunately knew exactly where Dr Bradfield was… and suggested he should be somewhere else for that particular time and it never caught up with him

![Sydney Harbour Bridge, Dawes' Point to Milson's Point, suspension design 1912 ... for tramway, vehicular and pedestrian traffic only. [and] (Cross section near tower), 1912 / J. J. C. Bradfield](/assets/images/episodes/2/a1471003ua1471004u.jpg)

With much finagling, Bradfield managed to convince the city’s politicians upon his return that it would be possible to build a similar single-arch bridge across Sydney Harbour that would not block its shipping lanes—a major sticking point for the city’s planners.

Yet the wheels of Sydney’s bureaucracy still turned slowly.

Back in 1916, the Honourable John Daniel Fitzgerald, a housing reformer and town planner, had introduced the ill-fated Sydney Harbour Bridge Bill to the Legislative Council and had said of the political football:

This bridge has been the sport of politicians for the whole of that period. It will open up those splendid areas of undulating land which are so admirably suited for the purposes of the building of homes of citizens, the housing of the happy and healthy people on that side of the harbour.

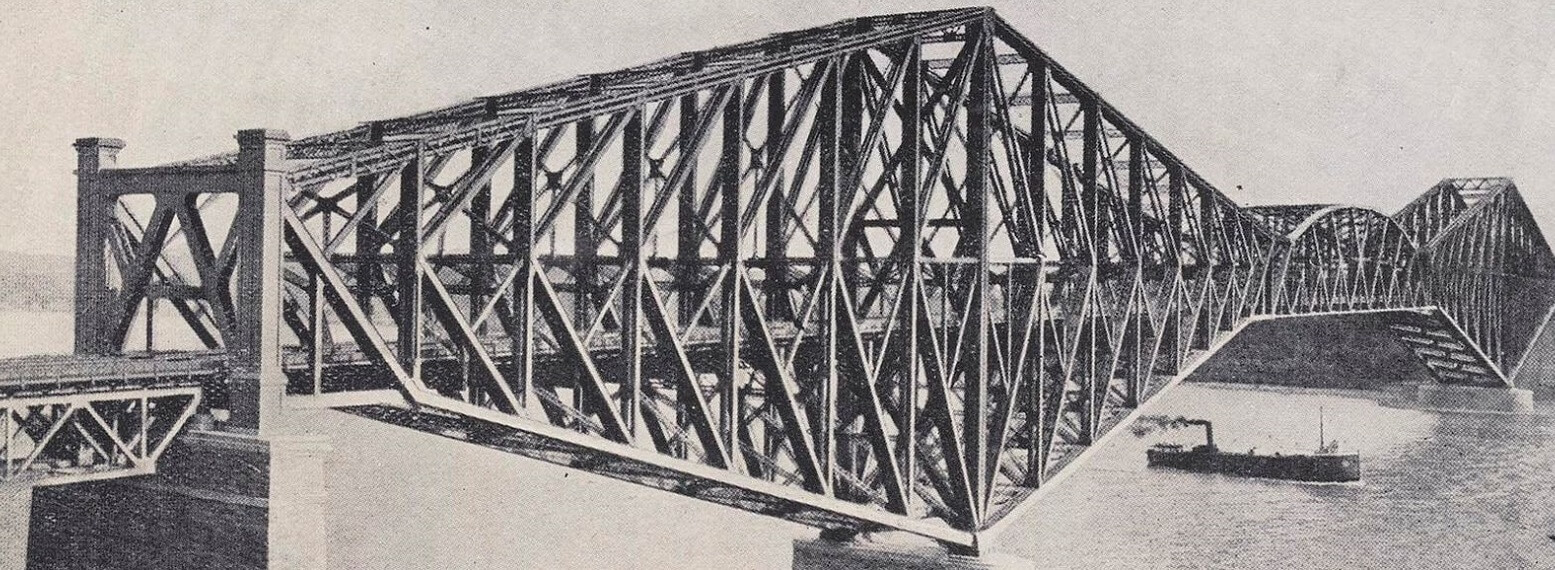

Finally, in 1924, the Harbour Bridge Act was carried. That same year, Bradfield recommended accepting the tender of Dorman Long & Co. of Middlesbrough, England. They had built a bridge in Tyne, an arch bridge that crossed the river between Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Gateshead in Northern England, that was very similar to the Hell’s Gate bridge.

![[Photograph no 2 McClintic Marshall products company tender B] from Sydney Harbour Bridge: Report on Tenders., TQ028863](/assets/images/episodes/2/c16532_0018_c_b_CROP.jpg)

![[Photograph no 11 Dorman Long & co tender A1] from Sydney Harbour Bridge: Report on Tenders., TQ028863](/assets/images/episodes/2/c16532_0047_c_b_CROP.jpg)

Dorman Long’s two-hinged arch with piers and pylons in granite-faced concrete was the second cheapest and was judged by Bradfield to be the best tender. He wrote in his report:

The tender recommended, for the two-hinged arch bridge with granite masonry facing, is my design as sanctioned by Parliament and as submitted for tenders… Due to our gallant soldiers, Australia has recently been acclaimed a nation. In the upbuilding of any nation the land slowly moulds the people, the people with patient toil alter the face of the landscape… They humanise the landscape after their own image…

Dorman Long & Co. would come to win more than 20 competing designs. Decades after the initial desire for a bridge to cross Sydney Harbour had first been given voice, the path was set for the most ambitious construction project that Australia had ever seen.

Bradfield announced his vision in a speech in 1921:

This is the engineer. He sees expresses passing in the air, Like toys adrift upon the breeze, And the common carts and wagons where The common seabirds soar and wheel. Linking the hills on either side, It dwarfs the city, ships and tide – A giant stiff with paint and pride – A dream translated into steel.

And so the visions of countless planners, designers, dreamers and engineers would shortly come to be realised—but it would be a task as enormous as the colossal structure itself. The process would take eight years, 6 million hand-driven rivets, 1400 labourers, and the lives of 16 workers.

In our next episode, we meet the people who built the Sydney Harbour Bridge.