The Bridge established Sydney as a truly global city, giving it a landmark to compete with any of the modern world’s great buildings and architectural structures. With the largest single arch of its kind, it was as instantly recognisable as Paris’s Eiffel Tower or New York’s Chrysler Building.

With the largest single arch of its kind anywhere on Earth, it was as instantly recognisable as Paris’s Eiffel Tower or New York’s Chrysler Building.

The ease of crossing the Harbour was instantly felt across the city. The population of the North Shore increased, and the ferry businesses, once such a roaring trade, declined.

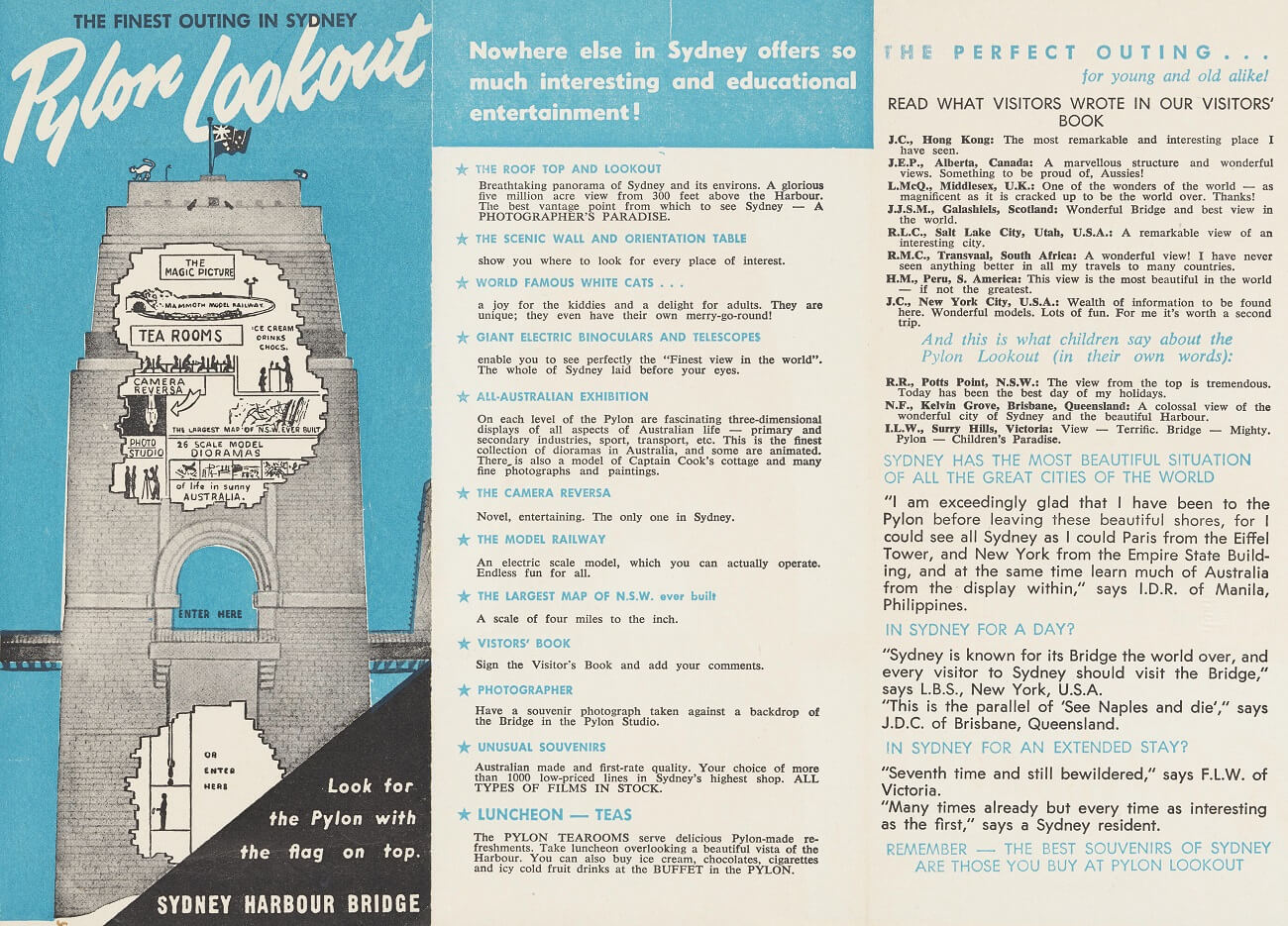

The Bridge soon became host to all manner of stunts and tourist attractions. The pylons were frequent visitors’ destinations, except during World War Two, when the Australian army commandeered them as machine gun turrets.

The southeast pylon opened as an extremely popular lookout, commanding uninterrupted views of the city and beyond to the horizon, impressing Sydneysiders with a panorama not seen before.

Between the 1940s and the 1970s, the Pylon Museum’s guidebook offered a window into the impressions of visitors from around the country:

![[Ephemera relating to the Sydney Harbour Bridge : including souvenirs of the ceremony of turning the first sod, the ceremony of setting the foundation stone, and the official opening ceremony], 1932, EPHEMERA/SYDNEY HARBOUR BRIDGE/1925-](/assets/images/episodes/5/c17272_0047_c_crop.jpg)

‘Height of happiness’

‘Wonderful’

‘Splendid’

‘Melbourne is still tops’

‘Still think the Yarra is better’

‘Can’t beat Adelaide’

‘Too many steps’

‘Need a drink, fine view, those stairs’

‘Too dark, can’t see a thing’ – ‘Well open your eyes, you mug!’

Once the Bridge was open to the public, the question of how to pay for its significant building and maintenance costs loomed.

The first tolls were charged for travel in both directions – an announcement the Lang government had kept from the public until just three days before the opening, hoping that any major displeasure at the news would be lost amid the heady celebrations.

Getting a family over the Bridge was, even in those times, an expensive undertaking as the cost was per passenger. It inspired some clever workarounds from enterprising citizens. Brian Pearson, a bridge engineer, devised one in the late 1940s and recalled:

Well, my earliest memory is crossing the Bridge, not frequently, but periodically, in my uncle’s motorcar with my younger sister and brother and mother. A blanket was in the back seat of the car so that the three kiddies could get under it. And as a consequence, the head count for travelling across the bridge was quite low… it was quite hilarious for us to be pushed under the blanket on each trip.

Toll collectors stood out in the open road to collect fares in the years before booths were built to shield them from the traffic.

Cars were charged a sixpence, or around $2 in today’s value, with threepence for each adult passenger and a penny for each child. A motorcyclist paid sixpence, a horse and rider threepence while cyclists and pedestrians could cross free of charge.

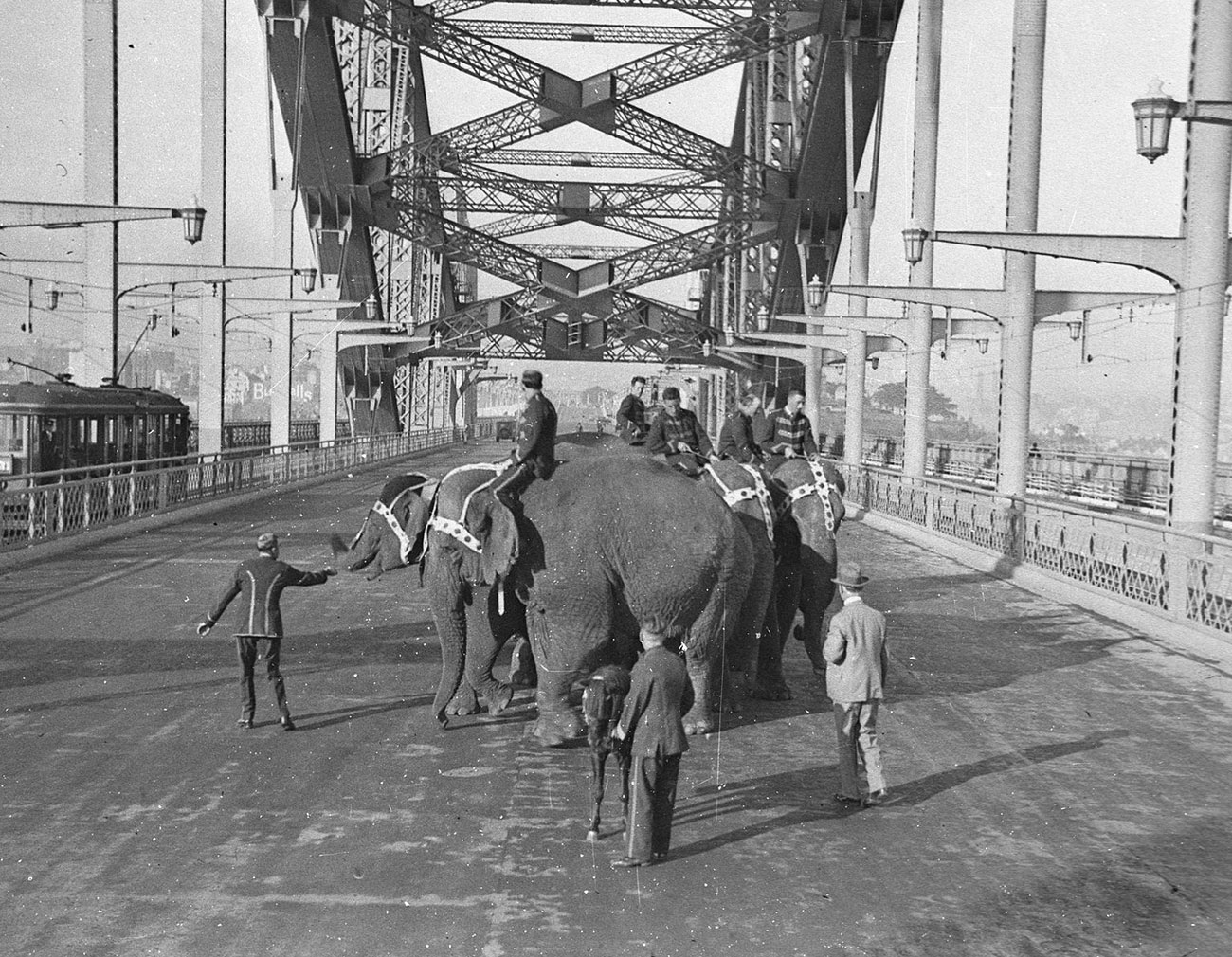

Not all travellers on foot, however, were exempted from tolls. In 1932, six elephants from the Wirth’s Circus Company were charged twopence each by the toll collectors.

By the 1980s, the tens of millions of vehicles which had by then crossed the Bridge—traffic which still numbers more than 150,000 cars daily in 2018—had recouped its original cost of $500 million in tolls. This did not, however, mean the end of paying to cross the Bridge. Instead, tolls were increased by the State Government to pay for the Sydney Harbour Tunnel, as well as for the ongoing costs of maintaining the Bridge.

Each year, engineers, ironworkers, boilermakers, fitters, plasterers, electricians, carpenters, riggers, painters and plumbers all labour for 200,000 work hours to keep the Bridge working at the total cost of $20 million. The Sydney Harbour Bridge was built with the intention to keep it in sound working order for a thousand years. Much of that responsibility is in keeping it free of rust from the salt air of the Harbour, and summer-heated steel beams can also cause the arch to rise and fall by as much as 18 cm.

Moreover, every five years, the exposed parts of the Bridge are repainted, a task requiring 30,000 litres of its trademark steel-grey paint.

The Bridge has always attracted thrill-seekers who were determined to climb it, irrespective of whether it was legal or not. In 1973, French high-wire walker Philippe Petit crossed on a wire suspended hundreds of feet up in the air between the two southern pylons.

There were tiny flags on top and the silhouetted ant forms of people arduously climbing the steep bow. It looked stamped against the sky, as if nothing could remove it. It looked indelible. A coat hanger, guidebooks said, but it was so much grander than this implied. The coherence of it, the embrace, the span of frozen hard labour. Those bold pylons at the ends, the multimillions of hidden rivets.

For the last twenty years, the slightly less adventurous have been able to take the guided Harbour Bridge climb over the arches.

The summit has inspired more than a few marriage proposals—at least one of which was ultimately refused, resulting in a quiet and awkward walk back down.

Over its 86 years, the Bridge has been a site of protest, civil action and celebration in Sydney. Its first closure was in 1946, when 20,000 people marched to celebrate Victory Day at the end of World War Two. Seas of people walked across the Bridge to mark its 50th, 60th and 75th anniversaries.

In May 2000, a record-breaking 250,000 Australians of Indigenous and non-Indigenous descent marched across the Bridge in the historic Walk for Reconciliation.

The massive crowd roared at the sky-written ‘Sorry’ above the Harbour, a sight in acknowledgement of the dispossession of Australia’s First Nations peoples—a dispossession which had begun with the arrival of the First Fleet in the very same place.

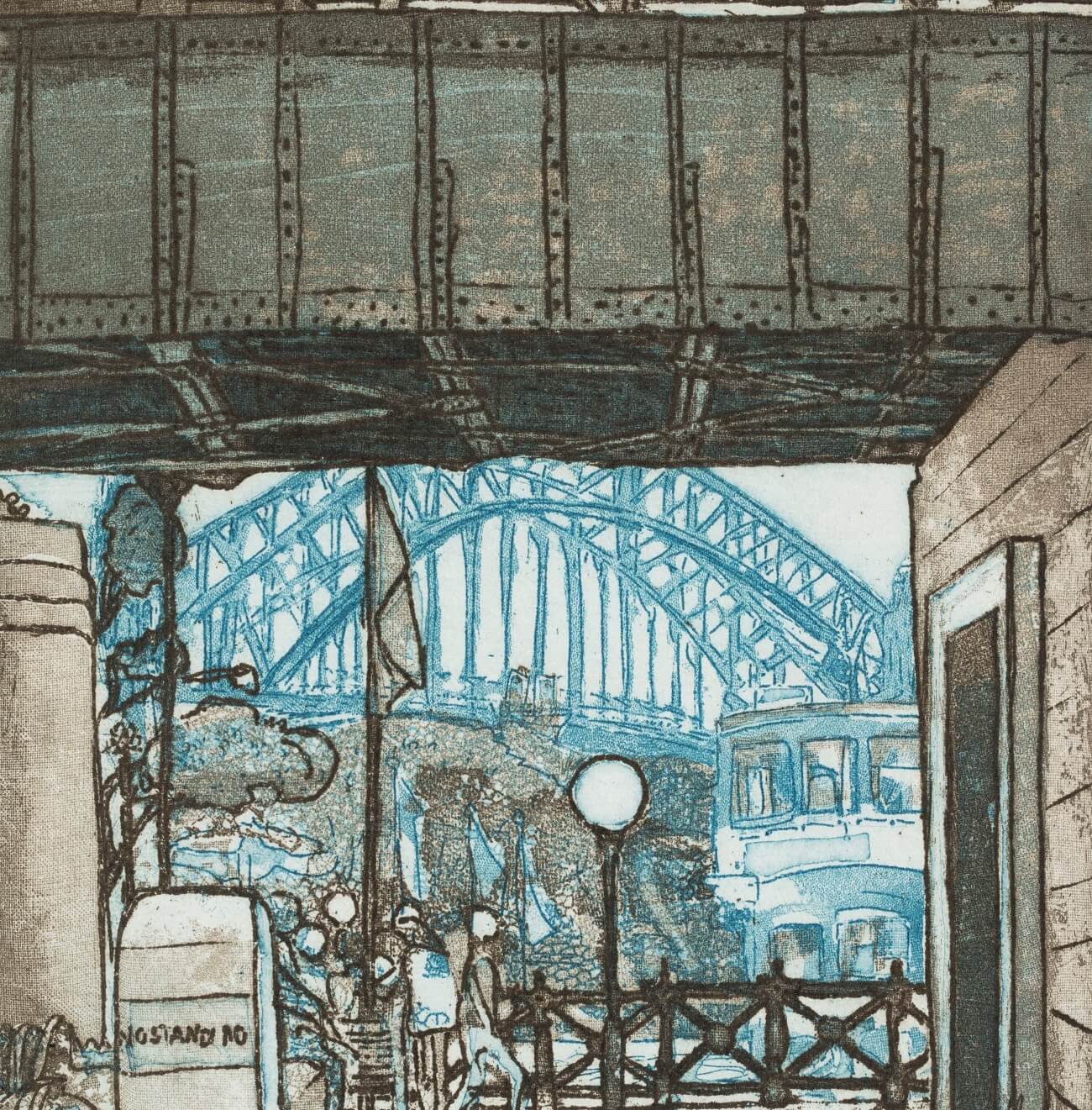

The natural beauty of the Harbour with each shore linked by the Bridge has inspired generations of artists such as Jessie Traill and Robert Emerson Curtis, and photographers Harold Cazneaux and Sam Hood captured the Bridge during its construction.

Jessie Traill was one of the first Australian women to work in line etching. Her art immortalised a remarkable record of the largest and most ambitious engineering project in Australian history.

What we see is a solid mass of concrete and intricate lace work of iron made more intricate by the play of light and shade; something that giants might play with as a child would with his Meccano Set.

Contemporary artists like Peter Kingston and Barbara Davidson are attracted to capturing its shape in the Harbour through etchings, prints and artists books.

Davidson in particular created many images of the Bridge, being linked to it through both her family history and fascination with the iconic structures:

My grandfather went to the opening because he knew Bradfield and my father-in-law walked the Bridge on the day it opened and took amateur movies. I think I’ve always been interested in the Bridge and I did have a book that my father had signed by Bradfield of the designs that were submitted by the Bridge. I think I’ve always had an interest.

![Sydney after Chagall / by Barbara A. Davidson.[Limited edition], 2002, 2002 H 2016/2134](/assets/images/episodes/5/artbooks_0002_crop.jpg)

Sydney is among the first places on Earth to welcome a new year, and staking out a hard-fought, prime viewing spot to celebrate the New Year’s Eve fireworks display on the Harbour has become a Sydney tradition. The two spectacular pyrotechnics shows at 9 pm and midnight each take months in the planning. The ‘countdown to midnight’ show costs $7 million and is over in only twelve minutes.

With eight tonnes of rockets exploding in the sky over the Harbour, cascading down the Bridge, Sydney’s New Year’s Eve fireworks is a raucous celebration of life, symbolising the city’s lustful soul.

Sydney Harbour Bridge carries more than cars and pedestrians. It carries expensive advertising and marketing, breathless superlatives from tourists, and the demands of Sydneysiders for it to be simultaneously a piece of gleaming costume jewellery and an unmistakable identity badge for their city.

It had taken 100 years, but the dreams and visions of colonial Sydneysiders—urban planners, engineers, politicians and workers—for a united Sydney Harbour had finally been realised.

The building of the Bridge played a huge role in the technical revolution of the 1930s and was seen as evidence of Australia’s industrial maturity in the mechanical age. It displaced the pastoral and agricultural way of life, ending the horse and buggy, and introduced the era of steel bridges, commuter trains and cars.

The Harbour Bridge sits in a redefined Sydney as a symbol of pride and national identity, holding a deep emotional resonance for many Sydneysiders.

The Bridge, as Ruth Park described,

…hangs there like the ghost of the wheel of fate, in a sky brindled with sunset, until darkness comes and vanishes away this remarkable shape, which is above all things, that sign of Sydney.